We Need To Talk About Scorpio

Nicolo Paganini & Aaron Copland

Are you surprised that Halloween, Día de Los Muertos, and All Souls Day are celebrated side-by-side in the early weeks of Scorpio? Let’s look at why that might be, take short rides through natural and cultural histories, and visit two very famous composers who shed light on this notorious sign.

Scorpions are older than dinosaurs and quite likely the oldest living animals on the planet. These spiders evolved over a span of 435 million years to live in deserts on every continent except Antarctica. In China scorpions can grow to nine inches. With pincers locked and tails “clubbing”, their elaborate mating dance can last up to two hours. However, scorpions do not then lay eggs. Like humans, they are ovoviviparous— scorpions give birth to live offspring!

Scorpions glow phosphorescent in the dark under ultraviolet light. Even their fossils glow after millions of years. Among some 1500 classified species of scorpions, only twenty-five can kill a human being. Their venom is a complex cocktail of toxins and other chemicals mixed within their control—depending on an intended target. Deathstalker venom is gaining notoriety as the source of scientific breakthroughs in diagnosing and treating cancers. Other scorpion venoms are proving effective in fighting malaria, treating arthritis, and managing auto-immune disorders.

Scorpio Rising

Since Scorpius is the Zodiac’s only constellation represented by a spider—an especially peculiar arachnid with a threatening stinger and crab-like pincers—it is not surprising that Scorpio generates more pronounced reactions than any other sign. The sign’s bad rap began, as the myth goes, when Orion, the hunter—a constellation that drops below the horizon as Scorpio rises—was stung to death by the spider. Pluto, the modern ruler of Scorpio, is associated with the underworld and the impulse to destroy—so as to renew. Pluto also brings to the surface for expression intense desires that may have been long-buried.

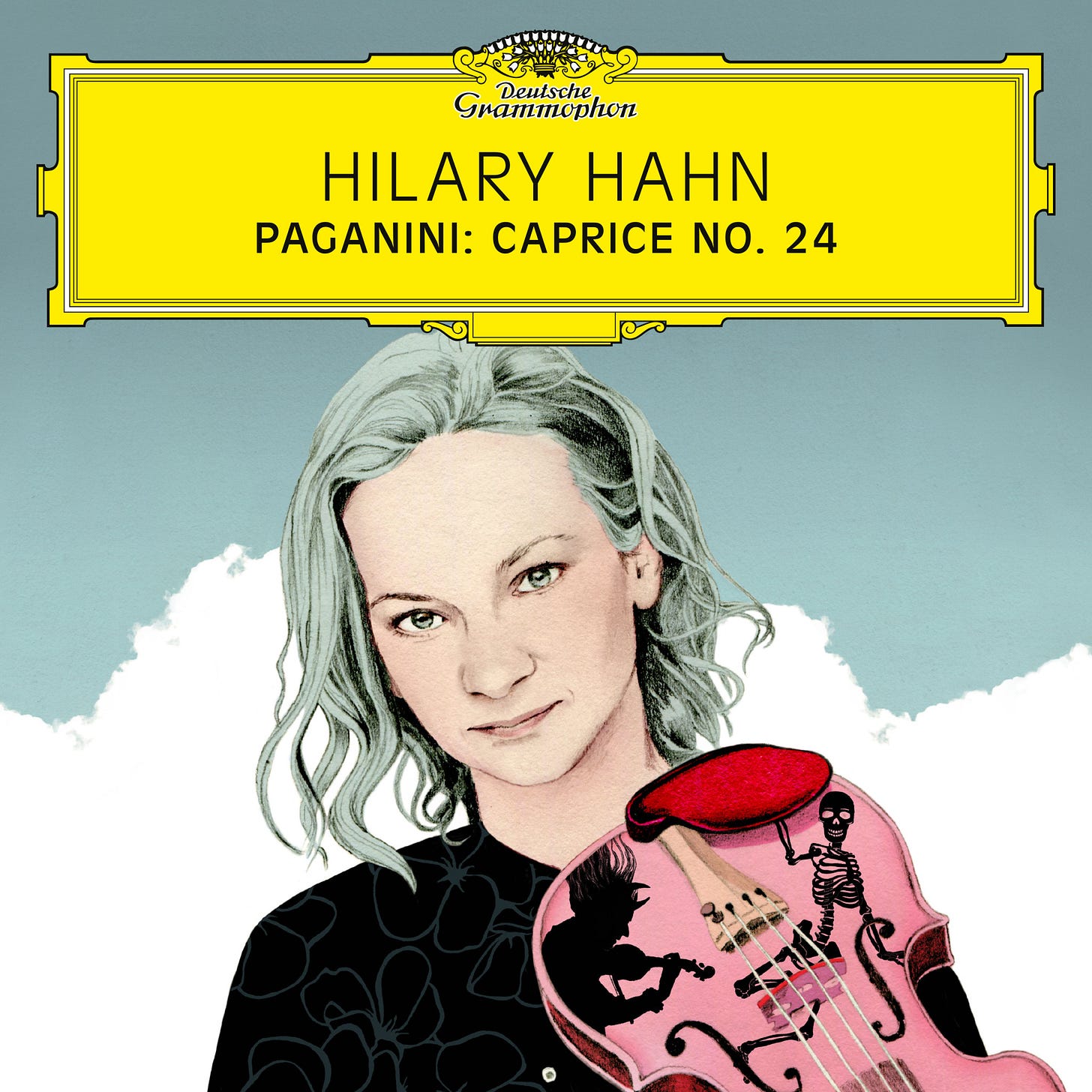

While the sign’s morbidity has a redemptive side, its nature is also nuanced in three ways that we will discuss further. Scorpio’s notoriety is well-earned—as the story of the violinist and composer Nicolo Paganini, born October 27, 1782, corroborates. Persistent medieval imaginating cast the character of death playing his violin, so Paganini’s Scorpio nature mapped well onto these fantasies.

Paganini’s exceptionally long fingers could play three octaves across four strings within the span of one hand. His violin, dubbed the cannon, was quite a bit louder than those of other virtuosos. His otherworldly technique resulted from accumulating every violin skill known by 1800 while adding tremendously fast scales and arpeggios, rapid shifting, double and triple stops, left hand pizzicato, string crossings, parallel octaves and tenths. He could bounce the strokes of his bow, play on a single string, and was unfazed when his jete or ricochet techniques actually broke a string. Such an unparalleled display was so startling that audiences were enthralled, shocked, and terrified.

Imperishable Greatness

Pallid, cadaverous, and spindly, Paganini is now thought to have been born with Marfan’s syndrome, like Abraham Lincoln. With unruly black hair, his ultra-flexible body and unusually shaped spine seemed to contort as though in the throes of death—while his exceedingly fast bowing and violent mannerisms were compared to a woman being thrashed! In Germany these seemingly impossible performances earned Paganini the nickname Hexensohn (Son of a Witch). Critics and writers everywhere dubbed him a sorcerer, a magician, or accused him of being a maleficus—having made a pact with the devil.

The remarkably innovative 24 Caprices, Paganini’s magnum opus, was composed in three sets between 1802 and 1817, a period of high artistic ferment. The publication of Goethe’s play Faust: Part I caused a huge sensation in 1805. Goethe’s character was a world-weary doctor of medicine and a scholar with knowledge of science and philosophy. Mephistopheles lures Faust with promises of occult knowledge available only to him. Faust’s pact with the devil leads to sexual conquest and infanticide. Frankenstein, the shocking Gothic horror landmark written by Mary Shelley, was published anonymously in 1818, soon after the completion of Paganini’s pinnacle 24th Caprice.

Napoleon I was crowned Emperor in the Cathedral Notre Dame de Paris on December 2, 1804. Enraged, Napoleon’s idealistic fanboy Beethoven, ripped up the dedication of his new “Buonaparte” symphony, renaming it “Eroica.” Napoleon’s sister Elisa, who wielded substantial power in Italy, was married to Prince Felice Pasquale Baciocchi. For ten years this strikingly handsome Prince took violin lessons while his wife carried on a romantic affair with his teacher—Paganini. Despite our Scorpio’s eccentric looks and a dark reputation, the violinist was a notorious womanizer who likely contracted syphilis. Paganini lost all his teeth In 1828, when the persistent disease was eventually treated with Mercury. According to DNA hair analysis published in 2012, Paganini finally succumbed to Mercury poisoning in 1840, a week after refusing a priest sent by the church to administer Last Rites. His unconsecrated corpse was moved from place to place languishing in temporary graves until 1876.

A greater contrast could not exist among Scorpio composers than between Paganini and Aaron Copland. The former may exemplify the reflexive wariness and illogical aversion associated with the sign, but a more interesting challenge is to understand Scorpio’s triple nature clearly observable in the latter. My astrological mentor Tim Troy described the three Scorpio types as—the spider, the eagle, and the gray.

Three Different Natures

The spider is strategic, perhaps devious, competitive, patient and possibly a master of tactical surprise in getting its way/prey. Their often colorful behavior and sense of theatre can distract the object of Scorpio’s interest from their intentions, as would a decoy, but with subtle powers at their disposal—including prolonged seduction—they are skillful success-oriented decision makers. The spider’s affinity for the sublime, ridiculous, and grotesque should be duly noted.

The high-flying eagle seems to possess superpowers allowing it to zero in on its prey and dive hundreds of feet to snatch with talons outstretched the hapless animal. Their majestic grace and perfect timing inspire awe. Modeling high-mindedness, the Scorpio native can reach goals by lifting up those in their circle with poetry, empathy, and soaring rhetoric. The powers of the gray, however, are veiled and mysterious, often giving the impression that nothing is going on with them despite a highly-tuned intuition and probing nature. Eluding the means to express the many nonverbal sources from which they receive information, words sometimes fail the gray. Yet, they are often effective anyway. The gray is quite capable of sexual abstinence and renunciation contrary to their Scorpio reputation as pleasure seekers for abandon.

Scorpio rules the genitals, and the native is often an intuitive, torrid, and very intimate lover seeking pleasure and deep connection. As the Age of Aquarius dawns, Scorpio is gaining from society’s movement away from religious relegation of sex solely to procreation, and toward sex-positivity based on the human need for pleasure.

Simply put, Scorpio represents sex, death, and transformation. Scorpio aids and abets essential change and should be seen as playing a near-heroic role in the greater scheme of human society, even if operating as a secret agent.

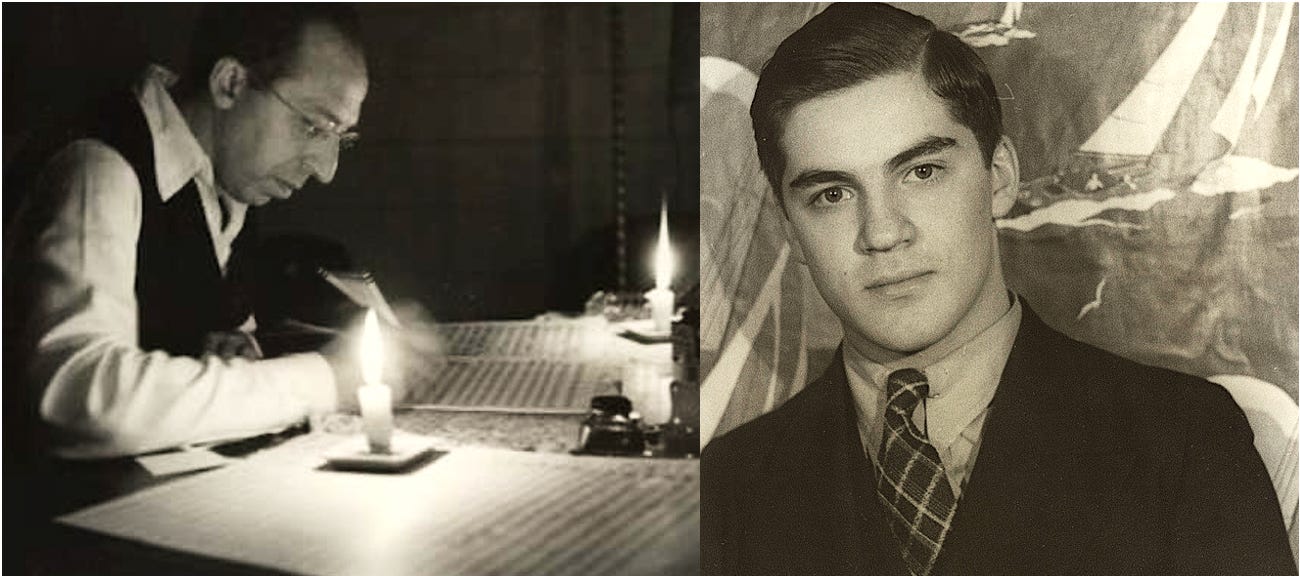

Copland, born November 14, 1900, was a likeable and good humored career composer known mostly for mid-century ballets of enormous vitality and tunefulness, as well as five film scores including The Heiress, which won an Oscar in 1942. He seemed to effortlessly draw from folk sources, Jazz, New England hymnody and the sounds of Latin America. His music fused nostalgia with progress to project an optimism that perfectly suited America.

Growing Pains

Copland’s formative years in Paris as a student of Nadia Boulanger were Les Années Folles, the Roaring Twenties. Yet he was celibate, geeky, and determined to be taken seriously. Copland’s music of this period, prior to 1936, may not be recognizable to many listeners as it is often harsh, angular, and strongminded. The work that raises his austere aesthetic to a pinnacle achievement is Piano Variations from 1930. Copland’s determined pursuit of modernism is fiendishly difficult to play and is a compelling exhibit of Darwinian evolution, each variation mutating with curious logic into another, twenty in all, and a coda. The pared down techniques of visual artists—etching, dry point, or wire sculpture—comes to mind. Ultimately however, Piano Variations betrays a certain Romantic heroism. In Copland’s own terms, it’s a barely concealed “Hebraic idea of the grandiose.” This excerpt played by Scott Dunn comes from a 2006 Jacaranda concert that paired Copland with America’s greatest composer Charles Ives.

Copland: Piano Variations performed by Scott Dunn

Ned Rorem, composer and raconteur, recounts a story of inviting guests to his Paris apartment in 1949 to hear Olivier Messiaen’s 24-year old star pupil Pierre Boulez play his own Second Sonata. Doubtless, this thorny music was truly extreme at the time and left many in the room quite undone. Copland bravely responded by playing his nearly 20-year old Piano Variations, which, according to Rorem, filled the room like an inspired force of nature, “thrown at the hostile chaos of the enfant terrible.” The work was actually a throwback, as his accessible new style emerged in 1936.

Liberation Below the Border

Before the Second World War, Copland toured Cuba, Mexico, Chile, Brazil, and Argentina giving concerts and hearing the music of pioneer composers in each country. A vacation in Mexico with 17-year old violinist Victor Kraft, Copland’s first serious boyfriend, challenged the 36-year old composer’s severe work ethic, as Kraft insisted the couple behave like newlywed tourists—clubbing until dawn, lounging on beaches, voyaging to Cuernavaca and Acapulco. A creative key unlocked a door and the score of Copland’s famously tuneful El Salon Mexico was dedicated to Kraft. Further evidence of his newly liberated voice was Danzon Cubano, another colorful orchestra piece. The lean sound and crisply delineated rhythms of the rarely performed 1944 original two-piano version, gains a sexy cat’s cradle excitement as a duet. This excerpt performed by pianists Liam Viney and Anna Grinberg is from Jacaranda’s comprehensive 2013 concert of music by five composers associated with “February House”, the short-lived crash pad, party house and historic queer landmark in Brooklyn.

Copland: Danzon Cubano performed by the Viney-Grinberg Piano Duo

February House

A three-story multi-tenant dwelling with a basement partially underground, a tall flight of stairs, and an oddly decorated façade, stuck out like a proverbial sore thumb from the surrounding brownstones at 7 Middagh Street. It would later be bulldozed for Robert Moses’ Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. This hotbed of Aquarius and Pisces was dubbed “February House” due to the many February birthdays of its inhabitants. Certainly, the combination of people and animals that occupied it was an exotic mix. The impeccably dressed composer Benjamin Britten and tenor Peter Pears, who had recently become lovers, lived there for a busy and intoxicating six months escaping wartime London as conscientious objectors to British armed forces. They were joined by the leading English poet W.H. Auden, and stripper/celebrity Gypsy Rose Lee (with her cook), who needed a getaway where she could write The G-string Murders, a mystery novel.

Writers Jane and Paul Bowles joined the literary scene at the house including George Davis, fiction editor for Harper’s Bazaar magazine, Klaus and Erika Mann, the queer leftist children of the bestselling author Thomas Mann, and novelist Carson McCullers.

Oliver Smith, a 22-year old art student moved in. His charm and good looks, as well as the company he was now keeping, led to a brilliant career as a stage designer. The Canadian composer Colin McPhee had recently returned from Bali after an extended study of gamelan music with his anthropologist wife working as a disciple of Margaret Mead. But McPhee was now facing hard times, as he had just come out as gay, and the couple was divorcing—so Davis invited him to join the “menagerie.” That term suited the household as there were many cats, and for a brief spell, a free-range toilet-trained chimpanzee. Davis made room for its carnival family until he got the chimp a job modeling hats for Vogue!

Salvador Dali, always accompanied by his intimidating wife and muse Gala, was a frequent visitor since Bowles was collaborating as a composer with the famous surrealist painter on a new ballet. Copland, who met Bowles in Paris as composition students, also partied at the house. They had been lovers briefly and gay confidants for many years after. Other party people included music critic/composer Virgil Thomson and Marc Blitzstein, composer of the incendiary opera, The Cradle will Rock. Regular visitors also included a 24-year old composer named Leonard Bernstein, the singer-actress Lotte Lenya, and ballet genius George Balanchine. Ireland’s leading poet Louis MacNeice hung out at the “ever so Bohemian” February House while he was wooing an American mistress, “raiding the icebox at midnight and eating catfood by mistake.”

Nationalism Fades

After many popular and patriotic musical successes in the Forties, Copland became fascinated by the postwar Darmstadt avantgarde turning his attention to twelve-tone technique and serialism. Unlike lesser-known composers such as John Cage and Elliott Carter, the highly visible, unmarried, left-leaning artist endured being blacklisted as a Communist sympathizer on the “Red Channels” list alongside Morton Gould and Bernstein. Fearing right-wing reprisals, President Eisenhower’s people had Copland’s music pulled from the 1953 inauguration ceremonies. After the turbulent intervening years, in 1969, President-elect Nixon’s people requested Copland’s music for a similar purpose causing him much personal distress by the association.

Grudgingly, he granted the Republicans permission but refused to attend the ceremony. Soon after, while ostensibly honoring Copland, Leonard Bernstein dismissed his friend’s tonally advanced works, such as Inscape, and adopted a patronizing tone at a time when he was famously romancing the Black Panthers and the radical left. Their spat went public, before apologies were made. The FBI investigation into Copland’s association with Communism would not be closed until 1975, fifteen years before his death.

Reading the Chart

The complexity and determination of Scorpio should never be underestimated, assuming that inhospitable rulerships of the moon, or Venus, are not limiting factors. Copland’s moon in Leo made him overly sensitive to criticism and generally uncomfortable in the spotlight, with a striving tendency to be in with the “in” crowd. However, Venus ruled by Libra is an exceptionally strong position for balance, justice, and partnerships. Copland’s Venus may explain his steadfast bond and ongoing sexual attraction to Kraft despite a cloak of public secrecy and every imaginable challenge to a relationship, on both sides, until his Kraft’s untimely death at the age of sixty when Copland was seventy-nine. Given his somewhat limited moon and extra positive position of Venus, Copland’s Virgo rising adds a front-facing layer of discipline and highly organized work ethic.

Copland was often quoted saying “Inspiration may be a form of super-consciousness, or perhaps of subconsciousness—I wouldn't know. But I am sure it is the antithesis of self-consciousness.” He adored extravagance but abhorred waste. Especially while studying in Paris surrounded by genius in all arts disciplines, Copland struggled to reconcile two equally compelling drives: to seek out and understand new experiences—the more challenging the better; and to keep absolutely true to himself no matter what happened.

As for his place and perspective on history, Copland wrote in his 1941 book Our New Music, that the “entire history of modern music may be said to be a history of the gradual pull-away from the [19th century] Germanic musical tradition”. Barely a trace of that tradition is apparent in his music, except for his late-career embrace of the movement begun by Arnold Schoenberg and his disciples, when Copland was coming of age. Now, some 80-years after his book’s observation, twelve-tone serialism has almost vanished from the contemporary music vocabulary, while key works produced by it slowly move into a phase of becoming classics—a canonization, if you will.

Could Inscape (1967), Copland’s poignant final orchestra work and a characteristic summation commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, be considered a key classic work representing this troubled period. All it would take to find out is the courage to perform it.