The Centaur With a Bow and Arrow month is a motherlode of great composers—mutable fire, a flashing skirt of tail, glistening horse flanks, god-like torso, and bristling quiver with arc et flêche, as the French would say—Sagittarius, whoa Nelly!

So, what about this archer’s mutable fire? Here are two spins around the zodiac wheel to help us land on the meaning of this elemental behavior.

Four elements—fire (Aries, Leo, Sagittarius), earth (Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn), air (Gemini, Libra, Aquarius), and water (Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces)—occur three times each and in the same order; while the three behaviors—cardinal (Aries, Cancer, Libra, Capricorn), fixed (Taurus, Leo, Scorpio, Aquarius), and mutable (Gemini, Virgo, Sagittarius, Pisces)—occur four times each in the same order.

Individuals born of “Fire” embody initiative, creativity, charisma, and propulsive ego energy. “Earth” individuals embody common sense, executive capacity, and organizing service energy. “Air” individuals embody intellect, balance, electricity, and social communication energy. “Water” individuals embody nurturing, regeneration, intuition, and otherworldly spiritual energy.

“Cardinal” expresses engaging behavior that thrives on attention, give-and-take, and exists for exchanging feedback. “Fixed” expresses dominating behavior that is willful, maybe stubborn, and best when strong-minded and principled. “Mutable” expresses adjusting behavior that makes creative calibrations in response to changing conditions.

The Archer

So, the mutable fire of Sagittarius elevates individual creativity to empower a humanistic spiritual community. It begins the wheel’s last quartet of elements.

Sagittarius spans from November 22—Saint Cecilia’s Day, which celebrates the patron saint of music, also remembered as the day President Kennedy was assassinated, to December 21—winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, and the date in 1968 when Apollo 8 was launched. On Christmas Eve the American space capsule was the first to orbit the moon—and its three astronauts were the first to see Earth rise above its satellite. On September 1, the first picture of planet Earth from outer space would grace the cover of The Whole Earth Catalog, a counterculture magazine and precursor to Google.

Mutable fire is vividly manifest as music by our main cadre of great Sagittarian composers—Ludwig van Beethoven, Olivier Messiaen, Benjamin Britten, and Jean Sibelius. This astonishing club of centaurs also includes Hector Berlioz, Scott Joplin, Jean-Baptiste Lully, and Giacomo Puccini—as different from one another as could be imagined, but with many commonalities as we will see.

It’s a Matter of Scale

To understand the Sagittarian command of the public gesture it is helpful to consider the so-called “greatest composer” Beethoven and his universally admired Ode to Joy. The story of how the finale of the Ninth Symphony got to a state of overexposure is best explored in more depth but suffice it to say that decades ago this symphony used to be performed like a sacramental offering on a special ceremonial occasions. Today It is more like a cash cow, a Nutcracker ballet, but performed all year round, everywhere, not yet all at once. The symphony, or just its detached finale Ode to Joy, has become a pops orchestra favorite requiring little rehearsal—costing less with a bigger return on the dollar, as long as there is public interest. Such overexposure is an understatement in Taipei where when you hear Beethoven, it’s time to take out the trash! Every day, a super bright electronic rendering of his beloved song Fur Elise calls to you like a dog in city-sized Pavlovian lab.

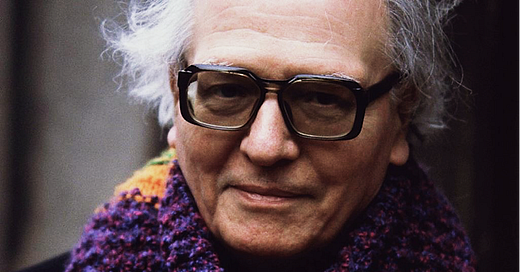

The reopening of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris December 8, 2024 coincided nicely with the 116th birthday of Olivier Messiaen, perhaps the most fabulously gifted French composer of all time. Telling stories through his ability to hear color and see music, while steeped in Shakespeare plays, as a child Messiaen was sequestered from WWI in the French countryside where he would begin a journey toward deep knowledge of birdsong. With the relatively new score to Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande as a birthday present, at age eleven Messiaen ensconced Debussy as his idol. More devout than his parents, the enterprise of Christianity and its musical roots in plainchant fascinated him. Greek myth and ancient Greek music would become another obsession. With the advent of musicology as a discipline—and field recordings—Messiaen learned what he could of non-Western music.

His personal story deepens when he was drafted as a soldier to fight in WWII, soon captured, and made a prisoner of war in Poland during a historically freezing winter. How Messiaen came to compose and premiere his most popular work Quartet for the End of Time for the prisoners in the camp is chronicled in For the End of Time: The Story of the Messiaen Quartet (Cornell University Press, updated with new material in 2006), and a novelization. When the war was finally over, this now-famous composer was uniquely qualified to compose a huge commemorative hymn, with his own text, for the liberation of the concentration camps. Chant des déportés, (Song of the Deported) was commissioned and performed for live broadcast by Radio France. After the premiere the hastily prepared music was lost, but re-discovered in 1991, one year before Messiaen’s death, then re-premiered in London three years later. When celebrating Messiaen’s centenary, Jacaranda gave Chant des déportés its 2009 U.S. premiere in Santa Monica.

Crazy Great Cosmic Party

Today, performances of Messiaen’s only symphony—a version of the Tristan and Isolde myth filtered through an opulent Sanskrit sensibility—are becoming more frequent. In 1967, when I first heard the Turangalîla Symphonie headphone-free on FM radio KFAC in my UCI dorm room, it was the most damnably loud and strange piece of orchestral music I had ever heard, easily surpassing the Rite of Spring. Since I tuned in-progress to the wild first movement, it would be about eighty minutes later before I reached the tenth and final movement to find out that I was listening to Seiji Ozawa leading the Boston Symphony’s first stereo recording on RCA by a composer then unknown to me. Also credited was Messiaen’s pianist wife Yvonne Loriod and her Ondiste sister Jeanne Loriod. My dorm mates were so flabbergasted they couldn’t complain.

Turangalîla’s technicolor exuberance and stratospheric level of difficulty has become a worldwide proving vehicle for orchestras wanting to show off their technical chops and sheer endurance. In 2017, the Orquesta Sinfónica Simón Bolivar de Venezuela was determined to stick the landing with its founding conductor Gustavo Dudamel in their hometown concert hall. The gargantuan piano part has seduced major artists, most notably Jean Yves Thibaudet, and the unlikely science fiction thrill of the electronic Ondes Martenot, a practical advance on the good-vibration-intimacy of the hands-free Theremin—has now compelled several generations of Ondistes devoted to the mysteries of playing the instrument’s grandest opus. In Caracas, classical music’s “it girl”, Yuja Wang, joined the Bolivars for her first go at this pianistic Parnassus, largely unheralded in the media. Cynthia Millar, the reigning queen of Ondistes, insured total command of her crucial part. Just months ago, released as a CD and on Spotify, DG returned to the Boston Symphony, with music director Andris Nelsons and the astonishing Ms. Wang having taken charge and nailing it “out of town.”

The short fifth movement at the center of Turangalîla is a fast cosmic dance entitled Joi du Sang des étoiles, Yeah, "Joy of the Stars’ Blood”! The lovers’ ecstasy imbues the constellations above them with the corpuscular fervor of their fateful passion as it surges through their hearts. The Sanskrit word Turangalîla is difficult to translate, but I have settled on: the transmutation of love’s power through time. This video will land you on “Joy of the Stars’ Blood”, but you will be able to hear and see the work in its entirety. Watch for Yuja’s volcanic cadenza right before the over-the-top ending.

The Grand Public Gesture

Like Beethoven, Messiaen was Catholic. Unlike Beethoven, Messiaen took Catholicism seriously, becoming an organist at Église de la Sainte-Trinité at age twenty-three and remaining at the organ console (when he was not traveling the world) until his death sixty-one years later in 1992. Like most Sagittarians, Messiaen loved “faraway places with strange sounding names.” He travelled to the French Alpine glaciers, New Caledonia, North and South America, and was married to Loriod, once his student, in Tokyo in 1963. Everywhere he went Messiaen notated the region’s bird songs, with binoculars, a big notebook, and a unique system of transcribing their wide-ranging frequencies. Not surprisingly, in his youth Messiaen hung out in Paris with surrealist writers and painters. At the Paris Conservatory—another life-long appointment—his first quiver of students, the best and brightest in France, were known as Les flêches, The Arrows. And so they were, leading legions of successors from around the world in spreading Messiaen’s mutable fire far and wide.

Messiaen fulfilled a commission by Andre Malraux, Frances’s powerful Minister of Culture—seven short movements to honor the dead of both world wars—that momentous year 1963. More sophisticated in every way than the hastily composed Song of the Deported, the premiere of Et Expecto Resurrectionem Mortuorum (And I Expect the Resurrection of the Dead) for brass, winds and percussion, in Sainte Chapelle was of monumental importance, as it was attended by General Charles de Gaulle alongside dignitaries from around Europe. The last movement “And I heard the voice of an immense multitude”, is the clearest possible expression of the Sagittarian mission. Here is a recording from the 2009 culminating concert of the OM Century, Jacaranda’s two-year centennial survey of Messiaen’s world—before, during, and after.

Club of Centaurs

To round out this group portrait, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem in 1962 with Latin and English texts (anti-war poems by Wilfred Owen) consecrated the new Coventry Cathedral destroyed in the WWII bombing of London by Germany. Jean Sibelius composed the tone poem Finlandia for a secret protest by the press against Russian censorship when Finland was a Grand Duchy of Russia. With the innocuous cover Impromptu, the work went public in Helsinki in 1900. A chorus was later added for the rousing final hymn, thought to be of folk origin but composed by Sibelius. The rousing heartfelt tune has been appropriated for hymns by American Christians, Italian evangelicals, as an anthem for Biafra the short-lived African state, and the patriotic song A Prayer for Wales. However, most importantly in Finland, Sibelius’s music galvanized national identity and helped the Finnish independence movement which succeeded in 1917 after the Russian Revolution.

So how do Lully, Berlioz, Joplin, and Puccini fit into this Sagittarian group portrait?

Born November 28, 1632, Jean Baptiste Lully had humble Florentine beginnings but possessed enough talent to excel at playing guitar, violin, and as a dancer. He was charming and spoke well enough to be taken to Paris to converse in Italian with the niece of Duke de Guise. He danced in a 13-hour spectacle ballet with the 14-year-old Louis XIV who was prophetically dancing the role of Sun King. The dancers bonded. Over the years, while Lully collaborated as composer with the famous playwright Moliere, he was promoted to the pinnacle music position in the Sun Kings Court. Lully composed dozens of motets, ballets, and operas, and invented the genre of incidental music to plays, most notably Le Bourgeoise Gentilhomme. Lully’s homosexual dalliances eventually displeased the King and caused a minor loss of status. Conducting his choral Te Deum with an imposing staff, as was the style, Lully forcefully struck his toe, refused to have it amputated when infection spread, and died of gangrene at age 54.

Berlioz, who started out as a guitar-playing, opium-smoking, nature lover, became the grand master of the public concert. Just the names of his most ambitious works express the scope of his Sagittarian vision. Grande symphonie funèbre et triumphale (Great Funeral and Triumphal Symphony) for tenor, trombone, double chorus, boys chorus, and orchestra celebrated the tenth anniversary of the 1830 July Revolution that established France’s constitutional monarchy. Richard Wagner attended and was bowled over. Commissioned by the star of November’s Scorpio Substack, violinist/composer Nicolo Paganini, Berlioz’s Romeo et Juliette was a dramatic symphony for soprano, tenor, bass, triple chorus, and large orchestra, that set translations of Shakespeare’s scenes in three of its seven movements. The oratorio L’enfance du Christ (The Childhood of Christ) employs seven vocal soloists, chorus, organ, and orchestra in three scenes “Herod’s Dream,” “The Flight into Egypt,” and “Arrival of Sais.”

Berlioz made the grandest possible arrangement of La Marseillaise, and his opium dream Symphonie Fantastique often surpassed Beethoven’s Fifth, and Mozart’s Jupiter for most performed symphony worldwide before the Ninth creamed the competition.

Vanguards and Virality

Scott Joplin’s 1911 landmark ragtime opera Treemonisha, the story of an African American freedwoman, rediscovered and reconstructed in 1972, contains a rousing scene “Aunt Dinah has blowed de horn” that engages the chorus in an infectious dance predating the landmark musical Showboat by 25 years. The all-Black cast extolls the importance of education to emerging civil rights. The enormously popular and prolific composer’s 1899 Maple Leaf Rag was the first sheet music to sell more than one million.

Finally, as I write this, Angelina Jolie has been nominated for a Golden Globe award in the role depicting Maria Callas, whose indelibly filmed Act II of Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca at Covent Garden in 1964 is considered miraculous, especially for the aria “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore” (I lived for art, I lived for love). Most opera houses today could not survive without Puccini’s La Bohème, Madame Butterfly, and Tosca on a rotating basis. When the 1990 World Cup organized the Three Tenors concert in Caracalla, followed by a sold-out Dodger Stadium in 1994, “Nessun Dorma” from Turandot sung by Luciano Pavarotti, brought the aria to such world-wide attention that it appears in commercials selling luxury items, and was even on Trump’s playlist for his October rally and dance-a-thon. Pavarotti’s performance of Puccini on The Three Tenors in Concert CD made it the best-selling classical album of all time.